We begin our story

with a brief review of Kermit Edwin Beary’s ancestry.

The earliest

ancestor our research has discovered was one Joseph Biery, a native of the

Canton of Bern, Switzerland. He

lived from 1703-1768. Although the

family is probably of French origin, it seems that one branch may have been

living in Bern as early as 1511. Joseph

was a man of position and property in Bern and Germany, and later in America. But these were trying times for

Protestants in Europe.

Between 1517 and 1750, during

Europe’s Protestant Reformation period,

hundreds of thousands of Protestants were severely persecuted, killed or even

sacrificed by Catholics. To escape the intense,

ongoing religious persecution, Joseph joined up with four brothers and three

sisters of the Doll family, another wealthy family who were suffering the same

experience. Joseph had met and

married one of the girls, Elisabeth Maria, in 1731 and they had a young

daughter.

The Dolls and Joseph felt

they needed to escape Europe and soon. Like thousands of others in their same position, they

formulated a plan. It wasn’t too difficult,

as there was already a well-established process for getting the persecuted out.

In fact in 1737 two other

adventuresome members of the Doll family had voyaged aboard the Samuel to Penn’s Manor in Pennsylvania

to see if they could make it. They

succeeded and wrote home to let the others know of their experience.

So in the summer of 1739,

the group, led by Joseph, made their arrangements, packed up, and then set out.

They and other travelers sailed by

barge first down the Rhine River to Rotterdam then switched to the ship Samuel to sail to Philadelphia, in the

British colony of Pennsylvania. Each

emigrant paid about $175 in today’s dollars. The ship made a brief

stop to pick up additional supplies in Deal, England, then proceeded across the

Atlantic. Eight other ships also

made the same journey that year. They

all sailed to the British colony because its founder, William Penn, welcomed

new immigrants seeking religious freedom.

During the three-month

river/ocean voyage, one of the elder Dolls died of illness. For Elisabeth, it must have been an

exhausting voyage, now pregnant with her second child and caring for a

seven-year-old girl. The long

journey ended in Philadelphia on August 27, 1739. Upon arrival Joseph and his fellow

adult immigrants took their oath of allegiance to the crown of Great Britain

and the province of Pennsylvania at the local courthouse. Several days later, Elisabeth gave

birth to Anna Maria.

The Joseph and Elisabeth

Biery family made their home in eastern Pennsylvania for several generations. They were leading citizens in the area

and played an important role in establishing the German Reformation church there. Beginning with Joseph’s great-grandson,

Peter, the family changed the spelling of their last name to Beary.

Peter’s son, Eli S. Beary

purchased a tract of land in Bethel, Missouri before the Civil War, and in 1870

moved his family there. Bethel

was founded as a Bible commune utopian colony in 1844.

Two generations later, Kermit’s

father, Harry Thomas, was born in 1889 in Bethel. During WW-I, he continued the Beary trek west, moving to

western Kansas with his new bride. And that brings us to the beginning of Kermit Beary’s story.

Kermit Edwin Beary, aka

Ken or KE, was born in the extreme northwest area of Kansas in the small town

of Selden on March 8, 1919 to Pearl Rae (McNeely) and Harry Thomas (Tom) Beary.

Interestingly, he was born exactly

two years to the day after his parents wedding day.

Seven

years later the family bought a farm in Edson, west of Selden. This was wheat and beef cattle country, but

also on the edge of the Dust Bowl. They were a poor family in hard times. Kermit received his basic schooling in Edson

with his two younger sisters, Bernice and Hazeldean. Observe the three young kids standing beside their two-bedroom

house complete with outdoor privy in Edson in the late 1920s. Kermit's

mother, Pearl, would put sheets in the bathtub to soak and then hung them over

the windows as big dust storms approached. There were many days they didn't go to school because dirt

was blowing so hard they couldn't see far enough to drive.

Kermit was interested in machinery as a child, and by seventh grade, his dad taught him to drive a tractor and a car. A year later he began playing basketball, and his dad started letting him drive to parties and basketball by himself. During high school Kermit even drove the school bus. He graduated from Edson High School, lettering in track and basketball in May 1937.

He

remained at home the first year following high school because he didn’t have

enough money for college. Wheat

harvests of 1932-36 had been the worst in history in Northwest Kansas, and this

hurt family finances. But after a

year working on a farm and with his mother’s recent inheritance, he was able to

start college in the fall of 1938. Kermit enrolled at Kansas

State College of Agriculture

and Applied Science in Manhattan, and majored in agriculture and economics.

(KSC became KSU in 1959.) He also

enrolled in the school’s ROTC program.

Kermit met his future

wife, Trudy, in Manhattan at a school dance. Gertrude (Trudy)

Phyllis Larson was from nearby Tescott, Kansas. The third youngest of Ralph and Neva Larson’s ten children, Trudy was born on August

25, 1921. She enrolled at KSC in

the fall of 1939, majoring in home economics.

Below we see the ROTC cadet and

couple during their KSC days.

Trudy

received a 4H scholarship, so tuition

was paid for. She earned her room

and board by working for a couple, taking care of the children, ironing, etc. Meanwhile, Kermit rented a room in a

house with a bunch of guys, and for money, he worked in a barn. He also worked on the Larson farm in

Tescott during the summer of 1941.

With World War II already

underway in Europe, plus his strong interest in flying, Kermit decided to drop

out of college early in his junior year to enlist in the Aviation Cadet

Program. Believing America would

soon be entering the war, there was a strong and growing trend in US colleges

for male students to enter service early and thus avoid being drafted into the

infantry. In July 1941 through his

ROTC program, Kermit received notice that he had been accepted into the Army

Aviation Cadet program. On 26 September

1941 he officially enlisted at nearby Fort Riley.

|

| Cadet Beary: Thunderbird Field, Glendale, AZ, Fall 1941 |

The Japanese surprise

attack on Pearl Harbor occurred during his flight training at Thunderbird

Field, probably increasing the class’ operational tempo plus student motivation

and stress levels.

Trudy withdrew from KSC

soon after the Japanese attack and continued her romance with Kermit via

letters and occasional telegrams. Unlike

today, Trudy says they did not talk on the

telephone, “The phone was expensive and had party lines where anyone could listen

in to your conversation.”

On 24 April 1942 he

graduated, receiving both his wings and a commission as a 2nd

Lieutenant in the Army Air Corps. (Only distinguished graduates were offered a commission, most

entered the Air Corps as Warrant Officers.) He received a photo ID card on his graduation day.

Three days later Kermit

and Trudy married in a Methodist church in Phoenix. Trudy first got herself out to Edson, and together with Kermit’s

parents and two sisters, Bernice and Hazeldean, they all drove to Phoenix. Ken had also sent a last-minute

telegram to Trudy’s folks requesting their permission to proceed with the

wedding. He received a go-ahead

call from them a short time later. The travelers from Edson attended both the graduation and the

wedding, which also

included flying buddy Jack Bestgen as best man and sister Bernie as bridesmaid.

The photo below shows the family

group at the Rose Bowl Motor Court in

Phoenix during these happy times.

|

| 2nd Lt Ken Beary with parents, sisters, and Trudy |

After the wedding Kermit and Trudy set off on a short honeymoon via Los Angeles and Yosemite Park enroute to his next assignment at McCord Field, Washington. But they lacked transportation. However, a solution was near at hand. Kermit’s best friends from the Graduating Class of 42-D, Lt Carl Bigger and Lt William Bingham needed to travel to the same destinations and were available to travel with them. Even more importantly, Carl was a bachelor and had a car.

He knew people in Los Angeles, as did the

newly wedded Binghams and Bearys.

So Lt Bigger volunteered to drive the group to Los Angeles. He first dropped off the Binghams with

friends, and next, Kermit and Trudy at the Phillips’ house (Trudy’s aunt,

Vivian and her husband Harold) in Wilmington. The Bearys also went on to visit other friends in the area.

Several days later Carl picked up the

Binghams and Bearys, and all headed north to their next duty station in

Washington State. On the way, they

visited Yosemite National Park.

The newly commissioned officers reported on 4 May 1942 to the Fourth Air

Force, McChord Field in Tacoma, Washington. There, the Bearys rented a one-bedroom closet that included

a kitchen, hot plate, icebox (real ice); they had to get water from the

bathroom down the hall.

Two weeks later, they both took a train to

Spokane, Kermit’s next interim assignment.

From Spokane, Trudy continued on

the train back to Tescott, Kansas. She soon applied for and was accepted for a munitions’

inspector position at the Kansas Ordnance Plant (KOP) in Parsons, Kansas. Located in the extreme southeastern part

of the state, the facility produced and stored artillery/mortar shells. It employed 7000 people, who worked in

over 700 buildings/storage facilities.

Meanwhile at McChord, the three lieutenants

began specialized training, transitioning to their combat fighter aircraft: the

P-40 Warhawk. They immediately began flying air patrols over the Puget

Sound area.

In December 1941, following Pearl

Harbor, the US Army initiated a secret base construction program in Alaska to

build two air defense bases, one on Umnak Island (Ft Glenn), and the second,

near the western end of the Alaskan Peninsula (Ft Randall) at Cold Bay. This program was anticipatory of a

possible Japanese incursion of the Alaskan mainland. To conceal their purpose, both fields were

organized as ostensible business enterprises concerned with fishing and canning.

The army used two cover names: Blair Fish Packing Company and Saxton & Company, whose peculiar canning equipment consisted of bull-dozers, power shovels and similar construction equipment. The top holding company for these enterprises was the Consolidated Packing Company of Anchorage, known in military circles as the Alaskan Defense Command! US Army personnel, disguised as civilian employees of the two companies, completed their assignments, and the airfields were declared operational by April 1942. These two air bases could help to better protect Alaska, especially the important US Navy base at Dutch Harbor.

The army used two cover names: Blair Fish Packing Company and Saxton & Company, whose peculiar canning equipment consisted of bull-dozers, power shovels and similar construction equipment. The top holding company for these enterprises was the Consolidated Packing Company of Anchorage, known in military circles as the Alaskan Defense Command! US Army personnel, disguised as civilian employees of the two companies, completed their assignments, and the airfields were declared operational by April 1942. These two air bases could help to better protect Alaska, especially the important US Navy base at Dutch Harbor.

Meanwhile, back at McChord Field, Lt Beary

and his compadres continued their air defense patrols. Their training however was curtailed

early because of alarming information gleaned by US Naval Intelligence in Pearl

Harbor on 20 May 1942: The Japanese warships of the 2nd Carrier

Striking Force were preparing to steam out of their Japanese Inland Seaport and

would proceed northeast 2800-miles toward the Aleutians. Formed around the light carriers Junyo and Ryujo, the task force had orders to attack the US Navy base at

Dutch Harbor.

This Japanese attack was to be a diversionary

one, timed to be simultaneous with their primary planned strike against US

forces on Midway Island, 1500 miles northwest of Hawaii. Having broken the Japanese radio code,

US Naval Intelligence immediately notified the US War Department (now Dept of

Defense) of the two plans.

In turn, the US War Department ordered the Alaskan

Defense Command (ADC), based at Ft Richardson, Anchorage, Alaska to prepare for

action. ADC’s air arm, the

Eleventh Air Force (11th AF), had responsibility for the air defense

of the Alaskan Territory. (Alaska

was an American territory at this time and not a state until 1959.) In terms of air defense assets, the 11th

AF was comprised of three fighter Squadrons: the 11th Fighter Squadron (11th FS), the 18th FS, and the 54th

FS. Most of their aircraft were

based at Ft Richardson, but the 18th FS was based primarily on

Kodiak Island.

On 22 May 1942 the commander of the 11th

AF ordered the 11th FS to deploy its P-40s to both secret bases. The 18th FS followed soon

after, sending a detachment of its P-40s from Kodiak to Ft Randall (see

deployment map below). Immediately

both bases established an aircraft alert posture and began daily air patrols of

the seas south of the eastern Aleutians. All appeared ready for the approaching Japanese task force.

In light of these activities, it is not

surprising that on 20 May 1942, Lt Beary received secret transfer orders. His orders had only a blank space for his

final station destination, but it was understood to be somewhere in Alaska. He was obviously to be part of the

secret mission buildup to the Aleutian Islands. The orders called for him to take a train from

Tacoma eastward to Geiger Field in Spokane and then to catch military air

transport up to an undisclosed location,

which turned out to be Ft. Richardson. He arrived in Alaska on 22 May 1942 and received another

restricted special order to proceed directly to the 18th FS

detachment at a second undisclosed location, probably Ft Randall. He arrived the next day. So this is how Lt Beary had suddenly

joined the war against Japan.

In early June 1942, six months

after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attacked the US military base at Dutch Harbor,

Alaska. The die was cast.

The Aleutians Campaign

The Aleutians, a long string of some

300 rocky islands and islets of volcanic origin with at least 57 known

volcanoes, stretch across the Pacific for thousands of miles. Thick layers of tundra or muskeg cover

the few level areas, rendering it mostly incapable of supporting an aircraft

runway. Equally important, the

Aleutians are subjected to some of the worst weather on the planet including

wind, rain, fog, and bone-chilling temperatures! One consequence of the severe climate: there are no trees.

Squalls, known as williwaws, often sweep

down from an island's mountainous areas with great force, sometimes exceeding

100 mph. The resulting columns of

spray and mist frequently resemble huge waterfalls. In the winter, williwaws could cause snow to be blown right

up one’s pant legs.

Distances within the Aleutians are of

continental dimensions. For

example, the distance from the 11th AF at Ft Richardson, to Kiska

Island is 1500 miles. US airfields

would eventually dot the islands from end to end.

In the predawn darkness of 3 June 1942, and

making excellent use of weather cover, Japanese carriers Ryujo

and Juny launched their first fighter raid against Dutch

Harbor. According to Japanese

intelligence, they believed the nearest field for land-based American aircraft

was at Kodiak, more than 600 miles away. Dutch Harbor should be a sitting duck for the strong Japanese

fleet.

In the Dutch Harbor attack, the initial

Japanese surprise was almost complete, but because of foul weather, the bombing

was anything but accurate. Nonetheless, some casualties and damage were inflicted. The photo depicts damage to the large

hospital complex at nearby Ft Mears. Unfortunately, the 11thFS/18thFS had

lost communications with Dutch Harbor at this pivotal time and never received

the warning until after the attack! Not a promising start to the defense of Alaska.

The following day, the Japanese got their

first introduction to the two secret fields. The so-called ‘canning companies’ went into action. First US operations took place early in

the morning when four Japanese Zekes and four dive-bomber Vals blundered onto

the Ft Glenn field while flying through Umnak pass enroute to Dutch Harbor. All four dive-bombers were shot down,

but two 11th FS P-40 planes and one pilot were lost too. There is no record of Lt Beary’s

participation, as he was at Ft Randall, too far away to likely get into the

action.

In summary, the two Japanese attacks

were a series of hit and run strikes. Damage to U.S. installations was modest and casualties few, but

the Japanese had demonstrated that they could once again bring the war to the

American territories.

Then, only three days later, a second Japanese task force of Army

infantry with Navy logistics landed unopposed and occupied the far western

Aleutians islands of Kiska and Attu. They had secured a foothold in the Aleutians to protect

the northern flank of the Japanese Empire.

These islands became the central

focus of the Aleutians Campaign.

In an immediate

response, the US War Department ordered additional forces sent to augment the 11th

Air Force in Alaska two heavy bombardment squadrons (2x B-24s), two medium

squadrons (32x B-25s), one fighter group (100 P-40s and P-38s), plus required

support. Initial deployments were

to Ft Randall and Ft Glenn, nearly 600 miles east of Kiska.

The 11th

AF had been built around a handful of pilots experienced in Alaskan flying. In the growing emergency of late May and

early June 1942, this nucleus was reinforced with pilots, who were hastily

dispatched from the States without full administrative or squadron operations

personnel. They rushed immediately

into combat with little or no chance for training under field conditions. This scenario would have Kermit’s name

written all over it.

There is little

information of Kermit’s exact assignment in the Aleutians. However, we have attempted to couple

those details, provided by Lt Beary’s daughter, Terry Huddle (Beary), with the

history of ongoing military operations.

There

are pictures of and taken by Lt Beary at Dutch Harbor.

It was a short flight from Ft

Randall to Dutch Harbor. Below we

see him and members of his squadron checking out the Army’s Ft Mears Hospital

and later attending a party with hospital nurses. The pilots were friends with a doctor, Capt Anderson (right

photo, first row far right, kneeling), who was not a member of the squadron. Ken even had assigned quarters at Dutch

Harbor. We remain uncertain as to

how many times he came to Dutch Harbor or why.

Kermit appears to

have spent most of the summer of ‘42 flying with the 18th FS at Ft

Randall. His squadron prepared for

upcoming air combat by practicing air defense and air strike missions in the

eastern Aleutians. He may have

stopped in Dutch Harbor as part of his missions. Below we catch him reading a book on a summer’s afternoon

during a respite. Note their

Quonset hut accommodations.

None of Kermit’s early missions were against the Japanese fortifications on Kiska and Attu, as Ft Randall was far too distant for the squadron’s short-ranged P-40s to strike Kiska and safely return. Instead the 11th AF, after deploying its large bombers to the two forward bases, used them for the long, 1000-mile missions against the Japanese-held islands. To provide escort for the bombers, the 54th FS transferred their long-range P-38s from Ft Richardson to both bases. The P-38 was the only fighter with sufficient range for this mission. A closer airbase was desperately needed.

Thus it would seem

that Kermit and his fellow P-40 pilots probably spent a rather slow,

uneventful, and frustrating summer of 1942 at Ft Randall and Dutch Harbor.

The establishment of Adak Army Airfield

gave the 11th Air Force a forward base from which to attack the

Japanese forces on Kiska Island,

245-miles to the west.

However, the construction of the airfield

was not without its challenges. Adak

had initially been inaccurately

surveyed to locate a suitable site. Upon learning this, a second survey team set out for Adak. They determined that a large tidal marsh could support the

field, because underneath the marsh was a firm

foundation of sand and gravel. A

Navy engineering team known as Seabees (derived from Construction Battalion:

CB) constructed a dike around the marsh and installed a system of canals to

drain off the water. They then

scraped off the topsoil to reach the gravel underneath. Additional gravel was put down and a

sand runway was laid down. By

early September the Seabees had completed enough work that Headquarters

declared the airfield operational.

Taking only ten days to complete, it

was an amazing construction effort! Below, view Adak just prior to Lt Beary’s arrival on station.

Almost immediately,

US bombing results improved and Adak proved to be a valuable asset. Lt Beary arrived on Adak on 12 September

1942, with detachments of the 11th FS and the 18th FS

from Ft Randall and the 54th (P-38s). He was still flying his P-40 Warhawk fighter, but he would soon fly with the Aleutian Tigers (11th FS). The remainder of 18th FS would relocate later from

Kodiak. Below, you can see Lt

Beary and his good friend, Bill Bingham (18th FS), standing by two

of the Aleutian Tigers. Their good friend, Lt Carl Bigger, was assigned

to the 11th FS.

The 11th

FS was better known by its nickname: the Aleutian

Tigers. The squadron’s first

commander was a Major John Chennault, oldest son of his already famous father,

Major General Claire Chennault, who headed the original Flying Tigers for the

Nationalists Chinese in Kunming, China. Obviously much taken by the “Flying Tiger” concept, John

adopted its symbol for his 11th FS in mid summer of 1942. With the opening of Adak, the 11th

AF decided to more efficiently combine and command its three US fighter

squadrons plus a newly arrived Royal Canadian Air Force’s (RCAF) 111th

Fighter Squadron, equipped with specially US-modified P-40s.

The new organization, the 343rd

Fighter Group (FG), essentially combined the fighter squadrons from their prior

bases and transferred them to Adak. Major Chennault was placed in charge and simultaneously

promoted: Lt Col Chennault had

assumed command of the entire 343rd FG. The group’s first missions were flown against Kiska by

mid-month.

On Friday, 25 September 1942, Lt Beary

participated in the first joint US-Canada

Adak air strike against Kiska.

Below you can see the actual map he used before and during the raid;

note the date.

A large force of US bombers plus US (11th

FS) and the RCAF (111th FS) fighters of the 343rd FG,

attacked the newly strengthened enemy garrison at Kiska Harbor. The raid strafed two submarines, setting

serious fires to several cargo transport ships in the harbor, and destroyed

eight Rufes – the seaplane version of the Japanese Zero fighter. Two of the eight Rufes were destroyed

in aerial dogfights. One was shot

down by a Canadian and the other was shot down by Lt Beary and Lt Col Chennault,

who both claimed victory for the same

one. According to Kermit, the Zero was already in flames by the time Chennault managed to fire shots successfully. But ultimately, as the higher-ranking

officer, Chennault received credit.

The mission succeeded in spite of heavy Japanese

harbor air defenses (see map above). For his actions Lt

Beary would later receive the US Air Medal. It had been only five months since graduation and his

wedding.

On January 8, 1943,

an article appeared in the Kansas Ordnance Plant (KOP) magazine, where Trudy

worked, entitled “Decoration to Inspector’s Flier Husband.”

During Ken’s time on Adak, he lived in a Quonset hut with fellow

officers. Here,

we see someone about to enter the cozy chateau. Note the lush landscaping

in the area and how well it’s been maintained.

Still the frequent weather groundings

at Adak pointed up the need for yet another airfield even closer to Kiska,

where momentary breaks in the weather might be better exploited. Here, in a photo sequence from 31

December 1942 at the US airbase, we see just how fast weather can change on the

island.

The island of Amchitka, some 170 miles

west of Adak and only 75 miles east of Kiska, was the only logical choice. The US Operations Plan issued in late

November 1942, proposed that the early capture of Kiska and Attu would be the

primary strategic objective. Fear

of enemy occupation of Amchitka, fanned by reports of Aleutian-bound Japanese

convoys believed destined for the island, drove this US action. Securing Amchitka became all-important.

On 18 December 1942 the US Joint Chiefs

in Washington approved constructing the new airfield on Amchitka if

reconnaissance indicated suitable airfield possibilities. That same day a Navy PBY airplane landed

a small party of Army engineers on Amchitka and found the island uninhabited by

Japanese. Following a two-day

survey, the engineers reported

that a Perforated Steel Planking (PSP) runway strip could be thrown down in two or three weeks and the main airfield could be built three or four months later.

that a Perforated Steel Planking (PSP) runway strip could be thrown down in two or three weeks and the main airfield could be built three or four months later.

Several days later the Joint Chiefs

ordered the invasion go ahead. On

12 January 1943 American forces landed on Amchitka unopposed. (Actually, most

Aleutian invasions by either side

were unopposed.) Construction was

not easy. Bulldozers and graders

had to hack away hills and fill gullies to level a landing field. When the Base Headquarters and its support

personnel arrived on 4 February 1943, about 500 feet of runway, plus huts and

other buildings, had been completed. The squadron historian recorded that it was a beautiful,

clear, sunny day. Very unusual!

It was time to move the US air forces

to Amchitka, and the 18th FS was selected to be the lead unit. Below, squadron pilots of the 18th

FS lined up beside the commander’s aircraft for a photo prior to their move to

Amchitka. Note the dry PSP runway;

wet PSP could be extremely slippery when wet.

Interestingly, we have recently

discovered that this exact plane exists today, tail number “33,” (the full

aircraft serial number is 42-9733)

and is still flyable (see inset photo). While still assigned to the 18th FS, the plane had

a taxiing accident on Amchitka on 3 March 1945. After the war it was moved to Adak as salvage and remained

there until a Bob Sturges received permission to retrieve it in 1969 and

returned it to the states to rebuild it. Numerous collectors have since owned the plane.

During airfield construction, Japanese Rufe

bombers (modified Zeros with pontoon under-carriage), based on Kiska, attacked

the island almost daily. It was

obviously impossible to anticipate when to send US fighters to intercept these

raids. So to better protect the

base build up, the Eleventh Headquarters directed a series of daylight air

patrol relays over Amchitka using

long-range P-38s. Each day the

last combat patrol would conclude just before sunset so the planes could return

safely to Adak before full darkness.

The Japanese soon came up with a

counter tactic. By timing their

own air strikes over Amchitka to occur at sunset, they could ensure that US air

patrols had already departed the island. The Japanese would thus be able to effectively bomb the base

construction without US planes interfering. Rufes could also fly back to their more westerly Kiska base

before dark because, at this high latitude and the two island locations,

sunsets on Adak occur some 20 minutes prior to those on Kiska. Pretty clever indeed! In fact the Japanese had successfully

used this ploy eight times before.

So,

on Wednesday afternoon, 17 February 1942, eight P-40s of the 18th FS

landed on Amchitka for the first time. As William Worden of the Associated Press wrote on site at

the time:

“To have an airplane land on a field

they built, on a island where no airplane ever landed in one piece before, on

the day after a Jap bombing—well, the combination spells a few minutes off from

work and some yelling that would do credit to the Minnesota stadium.”

“The other

planes were not far behind the first one, and in an hour, we had the most

beautiful little group of pea-shooters anywhere in the world. I know they look exactly like the other

thousands of fighters put out by that particular factory, but these are still

the most beautiful.”

Once the P-40s refueled and were tied

down for the evening, bad weather was on the way. Photos capture the mood pretty well. But after a very stormy, snowy night,

Thursday awoke to a bright sunny day. True to form, the Japanese attempted their ninth raid, but

this time the 18th FS sprung its own counter.

At about 6:00 pm, but prior to sunset,

all eight P-40s launched from their primitive runway at Fox Field (so named because the runway was long enough for only Fighters; see above). The eight aircraft climbed above the

cloud deck at 4000 feet and were divided into two flights of four planes each. Newly promoted 1st Lt Beary

was assigned to Flight One, flying on the wing of the Squadron Commander. (What a nice compliment to be selected

as the commander’s wingman.) Flight

One climbed to 10,000 feet while Flight Two climbed to 12,000 feet. Several thousand engineers, soldiers and

war correspondents began climbing the surrounding hills to gain a vantage point

and to anxiously wait to see what might happen. (See photo above.

Not very plush seating, was it?) But they didn’t wait long.

Alerted

by US Anti-Aircraft (AA) ground fire smoke puffs, the 18th FS

aircrews suddenly could view the incoming Japanese raid. P-40s had been flying out over the ocean

in a standard air patrol racetrack pattern

and were on their southeast leg when they saw the inbound raid. It was about 7:00 p.m., with sunset looming

at 7:27 p.m.

Flight

One swooped down to intercept two approaching Japanese Rufes. Major Clayton J Larson, the squadron

commander, known as Swede, and his wingman, 1st Lt Beary, led the

charge. The lead Rufe quickly

jettisoned its bombs, but to little effect. Both Beary and Larson fired on the attacker, resulting in a

stream of smoking gasoline trailing from the wounded plane. It continued to lose altitude

rapidly. Lt Beary’s final firing

pass caused the plane to burst into flames, and it finally plummeted into the

sea, only two miles off shore, as shown in the map below (designated as

#1). Larson and Beary’s firing

pass is illustrated below as the two small yellow triangles approaching the

white one.

Mr.

Worden wrote: “For us—thousands of us, watching from every hill in

the garrison area—the fight was simply repeated bursts of aerial gunfire,

followed by one bright comet of flame falling from a cloud. The wind was beginning to rise again,

but you could hear the yelling above the sound of it. These ground troops had been waiting a long time to see one

Jap die.”

The second Japanese attacker had broken

off his bombing pass and turned tail for Kiska. Flight One also saw him break and began closing on the

target. The Rufe flew out to sea

too, but generally paralleled Amchitka’s southwestern coast and headed

northwest toward Kiska. Within

several minutes, Flight One caught up. Larson, Beary, and Lt Stone made in-and-out passes as they

rotated their attacks against the fleeing target. During each, the Rufe executed diving, hard turns of 360-degrees

to try and evade. The pilot even

fired two ineffective gun bursts against Major Larson. After putting up a good fight, the

second Rufe took hits and plunged into the sea, some five miles west of

Amchitka’s northwest tip. Lt Stone

received credit for the shoot down. It was all over in fifteen minutes. The 18th FS landed at Fox around 7:30 p.m.

The ‘after-action’ report below lists

Lt Beary as a member of Flight One of the eight aircraft mission. Larson, Beary, and Stone all received

credit for downing the Rufes. This

day must have been one of Kermit’s most intense memories in his lifetime.

Here is a Kansas City Times article by

William Worden. The inset photo

shows Lt Beary being decorated much later for his actions. These two aerial victories would be the only two recorded by the 18th FS

during the entire war!

Within several weeks, the full

complement of the 18th FS and other fighter/bomber squadrons had

relocated to Amchitka, including the 54th FS. Within several weeks of the air battle

over Amchitka, Lt Beary received a Diploma from the School of WOAPs (Worn Out Aleutian Pilots). This

tongue-and-cheek award must have been much appreciated.

All were soon flying reconnaissance

patrols, gathering local weather data, and bombing Kiska. Bomb loads varied by fighter type: P-38 Lightnings

would carry two 500-pound bombs, and P-40 Warhawks, a single 500-pounder. These photos show the P-38/40 bomb load outs

and a successful air strike against Kiska. About 80 percent of the planes were usually operational.

Weather permitting and with Amchitka’s

Fox Field only 75 miles from Kiska Bay, five to eight fighter raids a day could

be dispatched. In the 18th FS,

half of the squadron might be assigned the 7:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m. shift while the

other half would take the afternoon shift. Ken flew four to five missions in the morning and then had

the afternoon off. This was

certainly the busiest, most exhausting, and dangerous period for him.

During that spring and summer, Amchitka

fighters and bombers flew some 1750 sorties against Attu and Kiska. Attu fell first. Many of the raids against Kiska caused

significant damage, but somehow the Japanese were always quick to repair the

damage.

During the US’ successful bombing campaign of March through July 1943,

the Eleventh averaged over 250 combat aircraft available on a daily basis; the

Japanese had only 15. No wonder

the US stopped worrying about Japanese air raids on Amchitka as the campaign

progressed. In fact, the Japanese

soon stopped scrambling Rufes to intercept US aircraft because they were so

out-gunned.

When it was over, the US had lost 35 aircraft to enemy anti-aircraft

gunfire, but 150 to operational accidents, attributable largely to the poor

weather! That represented the most

alarming ratio of weather losses to total losses in all WW-II: 81%. Sadly, Lt Beary’s good friend and member

of the 11th FS, Lt Carl Bigger, died during a landing accident on

Adak on 22 April 1943. US

replacement aircraft were continually flown in. Of course, all 15 Japanese aircraft were destroyed.

Battle of Kiska: “Operation Cottage”

When the US invaded Kiska on August 15, 1943, the weather was

strangely clear and the seas quiet. Amazingly, the 35,000 Canadian and US soldiers that landed

were unopposed!

Then, after several days of scouring the island, they discovered that

the Japanese Navy had evacuated the Kiska garrison of 7000 men several weeks

earlier, under cover of fog. Somehow

the US had not observed what had happened and had bombed abandoned

positions for almost three weeks without suspecting the Japanese were no longer

there. To be fair, some aircrews

reported seeing trucks parked along the roadways and they never seemed to move.

Commanders failed to conclude the

obvious. Amazing!

Regretfully, the Japanese may have been

absent, but Allied casualties during the invasion numbered 313. All resulted from friendly fire, booby

traps, disease, or frostbite. As

with Attu, Kiska presented an extremely hostile environment in more ways than one. On 24 August 1943 the US invasion

commander declared Kiska secure. The

Battle of the Aleutians had ended.

The 18th FS remained on Amchitka long after the Aleutian

Campaign. In fact it was the last

fighter or bomber squadron to leave the islands, departing on 28 March 1944. That period must have been very

eventless and boring.

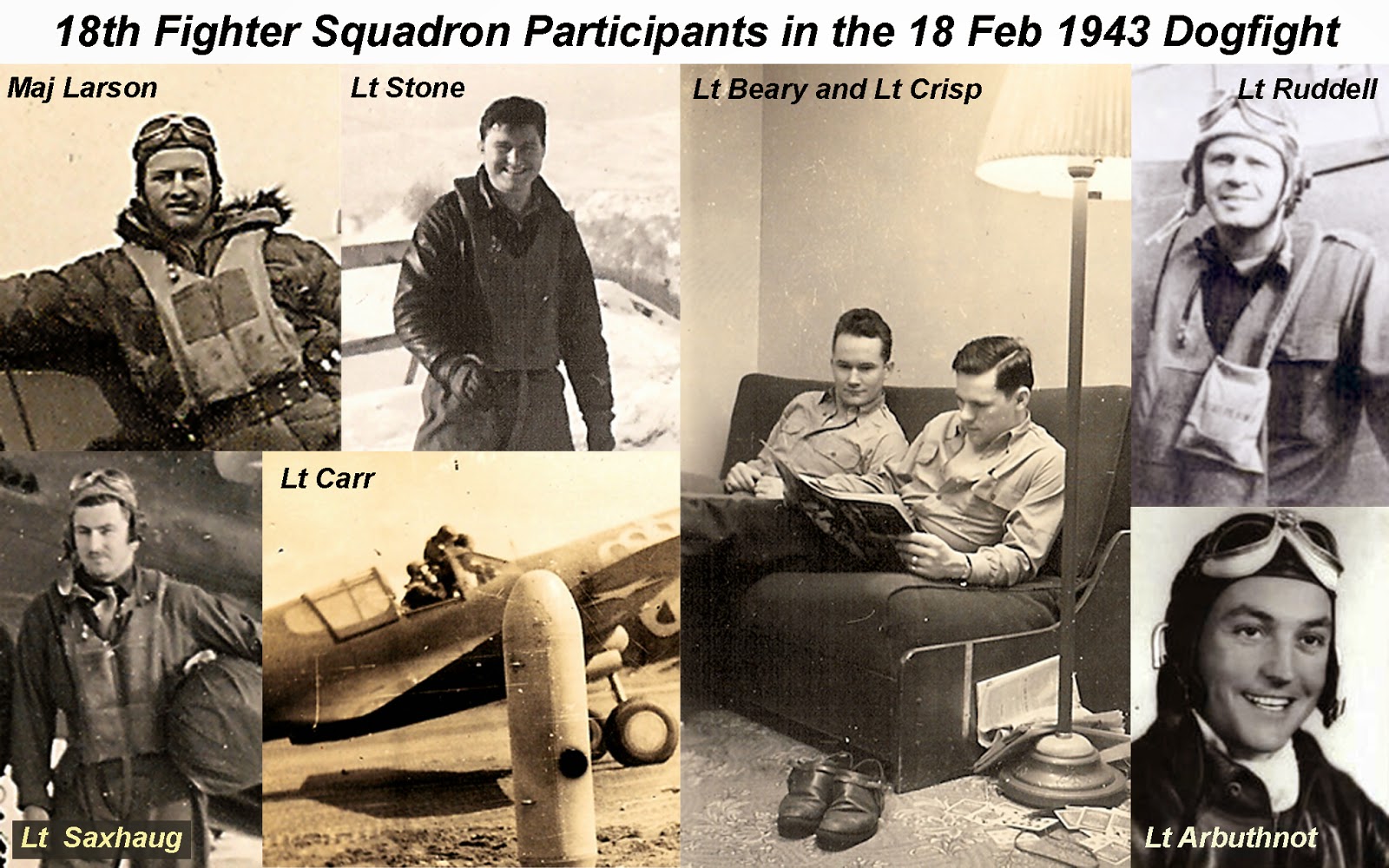

However, Lt Beary had long since departed Amchitka, having completed

his assignment by mid-April of 1943. He received Special

Orders Number 46, dated 14 April 1943, to transfer to Mitchel Field, Long Island. Joining him would be Maj Larson, Lt

Stone, and Lt Crisp, all of the famous air battle on 18 February 1942! Lt Bingham also joined the travelers.

Kermit had served in the

Aleutian theatre from 22 May 1942 to 9 May 1943, not quite a year. He

flew 60 combat hours and had a total of 120 hours in the P-40 in the Aleutian

Islands. His medals include:

- Air Medal

- Distinguished Flying Cross

- American Camp Medal

- WWII Victory Medal

- American Defense Service Medal

- Asian-Pacific Campaign Medal, and

- The Meritorious Unit Plaque

The following chart

summarizes Lt Beary’s succession of assignments with the 18th FS in

the Aleutians. Note how closely

his sister P-40 squadron, the 11th FS, is intertwined. In late May 1942, both squadrons were

detached from their primary bases to the two new, secret locations. This fact helps to explain why it is a

bit difficult to track Kermit’s assignments during the summer of 1942.

Also,

listed below are Lt Beary’s 18th FS commanders while he was stationed

in the Aleutians. Interestingly he

had nine leaders during his time in theater, but several had multiple

opportunities, and only Captains Gayle and Larson held the position more than

two months at a time. Otherwise,

the average tenure was very short, weeks to a month!

18th FS Commanders

1 Lt

John C. Bowen, 24

Apr - 28 May 1942

Capt

Charles A. Gayle, 28

May - 03 Aug 1942

Capt

Clayton J. Larson, 03

Aug - 12 Sep 1942

Maj

Charles A. Gayle, 12

Sep - 18 Sep 1942

Capt

Louis T. Houck, 18

Sep - 02 Oct 1942

Capt

Joseph S. Littlepage, 02

Oct - 29 Oct 1942

1 Lt

Albert S. Aiken, 29

Oct - 10 Nov 1942

Capt

Clayton J. Larson, 10

Nov 1942 - 05 Apr 1943

Trudy had returned to live with her parents in Tescott after being laid off from he KOP inspector’s job in Parsons. When Kermit arrived in Seattle, he immediately wired her a telegram.

He did pick up Trudy in Edson, and they drove East to his new

assignment at Mitchel Field on Long Island, New York.

By fall they moved on, first for a short assignment at Westover Field,

Massachusetts and then in the winter of 1943-44, to Hillgrove Field, near Providence,

Rhode Island. While in New England

they had an opportunity to join up with Trudy’s older brother, Lt Dean Larson, who

was in transitional bomber flight training in New England prior to his

departure for the Philippines later that fall.

Trudy’s photo shows Lt Beary and Lt Dean Larson, his wife Lola, and

their son, David. This 1944 serene

summer scene is on Old Orchard Beach, Maine, such a dramatic contrast from his

months in the Aleutians. Prior to

the war, the two families from central Kansas could never have anticipated this

scene. WW-II did that!

The photo offers no clue as to how suddenly things could turn upside

down. Tragically, Dean would be

killed in air combat over the Philippines within eight months. Similarly, Trudy and Dean’s older Air

Corps brother, Lt Don Larson, was presently a POW in Mindanao. Sadly, in early September 1944, he would

also be killed in the Philippines. A US Navy submarine torpedoed his Japanese prisoner ship

enroute to Japan, thinking it to be a Japanese troop carrier.

Kermit Beary had experienced a fascinating span of two years (1941 -

43): From enlisting at Ft Riley, to flight training, to marriage, and to his

last aerial combat in the Aleutians, all within 19-months. Who could have ever guessed? This period had certainly changed and

influenced what Kermit would do in the future. World War II changed lives forever.

Kermit continued his military service beyond WWII, later serving as a

fighter pilot during the Korea War.

He retired from the USAF in 1967, following a 25-year career. Many of his later assignments involved

fighter aircraft weapon system testing and development.

As an Air Force wife, Trudy’s accomplishments did not garner her

medals and a feature in the local paper, but she served just the same. Like Kermit, she moved continually

around the US and even overseas to Japan.

But while he was responsible for transporting his personal gear and uniforms, she moved entire

households and raised three silly characters, all while presenting herself as a

proper lady.

Once the girls were grown and on their own, and while working at his

second career as an engineer for Hughes Aircraft in Canoga Park, California, Kermit

returned to the Pacific Ocean. But

this time, instead of flying over it in a fighter plane, he sailed upon it in a

boat. He and Trudy became sea

mates and enjoyed years of adventures up and down the west coasts of America,

Canada, and Mexico. And later, in

their camper, they roamed the country, visiting friends and relatives, and

amusing each other all the while.